David Greenberger

creator of The Duplex Planet and solo artist

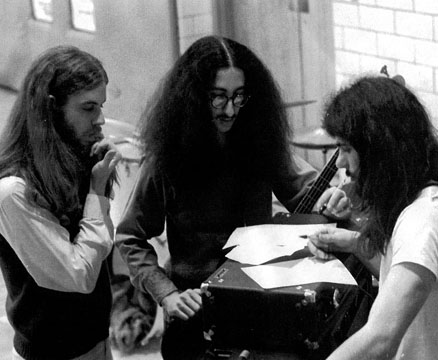

David with band "Calico" in 1972. Left to right: Mark Dodge, David Greenberger, Giles Ponticello

November 29th, 2003- At a Local Coffee Shop in Atlanta, Georgia

LK: Talk about The Duplex Planet.

DG: I’ve been doing it for twenty-five years. Started in 1979. Probably the best way to talk about what it is, is to talk about what led up to doing it. I didn’t realize this at the time, this is in retrospect, but in the mid-seventies, I joined an art school in Boston. I studied painting, and then did this trip out to Palm Springs for my grandmother. She flew me out there, and I was going to get her car and drive it back to Chicago for her, then she was going to fly back. She did this with all of the grandchildren. While I was there I met this friend of hers, this guy named Herb. I took to hanging out with Herb for the couple of days that I was there. Herb and his wife were childhood friends of my grandmothers. The thing for me that was kind of cool, is that I was in my twenties, and I was hanging out with this old guy who I never knew before. It took me a while to realize that this is what triggered it, but when I got back home, I stayed in touch with this guy for a while. Mostly I wanted to find a way to do “that” again, but I didn’t know exactly what “that” was.

What I had found a way to do, what I was doing, was meeting people who were old, who were not related to me, so the same dynamics of a relationship where you start at some point, and move forward were in place. Almost everybody that I knew who was old, up until that point, was related to me, and there is a dynamic already in place, and your own mortality in witnessing an older generation decline. You get caught up in your set roles. You were The Kid, and now you’re still The Kid, and you get tied up in mourning the loss of who somebody used to be. Feeling bad that they can’t do whatever it was that they used to do.

So, getting to know Herb, it was liberating in this quiet and gentle way. It was the same steps that any relationship would follow. You talk, you hit it off, you joke around, you head straight to your background and talk about it, and little by little the things emerge. That’s what I was responding to. So, I took a job at a nursing home, as an activities director. I thought maybe I could teach painting, I didn’t know what I could do. I found as soon as I stepped into this world of this nursing home, it was a 45 bed all male nursing home in Boston, in an old converted house the way nursing homes were before. As soon as I stepped into this world, it was completely riveting to me personally. It touched on a lot of my own interests and foibles, and so for me as an artist, I really felt like I had found something. I didn’t know quite what it was, but that it fit me better than anything else ever had. So I consciously stopped painting. I’d been painting regularly, and I thought, “ I need this to somehow become what I do. I don’t know what that is, but if I have painting somehow as my outlet, this other thing will be an adjunct or just something else.” So it was a conscious thing.

I did right away start writing stuff down that people would say. I did have a long standing interest in the way that bits and fragments of a conversation, or an overheard dialog can be really resonant when taken out of the air and put on the page, as opposed to what somebody means for you to put on the page. Like what I’m saying right now is sort-of meant for that, I’m talking in a controlled way. But when it’s not that, these things spring to life; somebody’s character rather than the substance of what they are trying to say. I always like those character-rich things, and the environment of this nursing home was filled with that.

So I just started writing things down, and talking to people, and I was supposed to be an activities director, making it up as I went. It was that time in my life in your mid-twenties where everything all mixes together, life and love, and art and bands, I was in Boston and in a band, and it was all one. I’d take the guys from the nursing home to see the band. It was all mixed up.

The magazine I started first. It was just stapled in the corner, 8 1/2 x 11 sheets, typed up. But I called it The Duplex Planet right away. It was not particularly glamorous, just these pages stapled. I didn’t know who it was for. It was my own interest, and someone was paying me minimum-wage to do this thing. I already liked writing this stuff down, and now it’s my job. I got everybody from the home together one afternoon when I had this first issue, and passed out issues to them, and they could have cared less. It didn’t mean a thing to them. Because it was these little asides, “I met a cranky cop down at Jamaica Pond…” It would be some line, and they would think, “So what? There’s no coffee? No cake? You brought us in here for this? There’s no cake?” They wandered away. But that night, I took copies home with me. I Xeroxed them there, they were not printed, and friends read it, but they read it as literature, with these characters coming to life. Instantly I thought, these people who are in it are there to form a relationship with, they are to be my friends, and this thing is the outlet that allows me to explain this alternate and I think missing dynamic of how you can relate to the elderly, to everybody else.

Within the first five issues it took on this shape, I was getting them printed then, and set out to create some sort of buzz for it. Articles would appear about it, and I was getting the word out. People were finding out about it. I moved from Boston five years after I started it, and by then I had maybe fifty issues out. I kept going back there. I kept finding other ways to do stuff. The thing that I liked about doing it as a periodical, was that it mirrored the way that you interact with someone that you see just once in a while. So, these characters would be sketched in little by little, because it was the same people over and over again. So each time, depending on who the reader was, they would respond to different people in it. The same way anybody would with anybody else. So I liked that aesthetic - that it mirrored this process, so that over a period of time somebody would feel like they were getting to know these characters.

I knew it was working when the first people started to die, of course. I’d do an issue, maybe collecting stuff together, and I would hear somebody say, “Herbie’s dead?” But they didn’t know him in person. I was trying to make this connection. And as time went on I moved to upstate New York, and the nursing home eventually closed after that, but I kept finding other ways to talk to people in other places, and I also found I needed to expand what I was doing outside the confines of a little book people would have to send a check in the mail to get. It was making limiting sorts of demands on who the audience for this was ever going to be. I felt like, and still feel like it speaks to anybody. It’s about this common human experience of aging. It’s fairly friendly stuff, there’s a lot of different ways in. So I knew I needed to have books and put things out in other ways. That all began happening in the early nineties. There have been some book collections, and then there was that Fantagraphics comic book adaptation. All of these were ways to get the material across. I feel like my allegiance is to the underlying material rather than any one particular media. If I know comic book artists, then I’ll do it as a comic book. This stuff is resilient, and can be transferred into many different forms. Plus I like the challenge for myself , to work in other areas like that.

The biggest change for me was originally doing talks about it, or doing readings, and having that develop into monologues with music. That’s really the area I am most energized by. I’ve done a number of these cd’s over the years. But Mayor of the Tennessee River was the first that was a regionally based project. I’ve done this with the Shaking Ray Levi’s. They had heard of me, and we had a mutual friend in Michigan, so they brought him down to Chattanooga, and we rehearsed for a couple of days, and we had such a great time that later they brought me to Chattanooga for a couple of weeks and I had a routine. Every day I would go to a different place and talk to people, and then go back home with that material. I would go back through it and figure out where the stories were, what they were, and they worked on the music that ran through it. I’ve done that in a few places now. I’ve just done one in Portland, Oregon and another one in Pennsylvania. I like what music adds to it. It expands the emotional pace of the thing.

LK: Talk about some of the music, art, or writers that influenced you at a very early age.

DG: One of the guys that influenced me that would have very little to do with the content of this, was Ed Ruscha. He’s probably in his late sixties now. He came into prominence in the 1960’s, and there’s very familiar images that he did. They were silk-screened images of gas stations with kind of a forced perspective. But what really had an influence on me was that he did little books. He was the first person that I knew of that was doing artists books. He did a whole series of these. 26 Gas Stations. They were like really dry titles, and he would go out and shoot really dry photos. I remember seeing an interview with him, and he was saying how thrilling it was having this stack of these books from the printer in front of him. I responded to something about that. The idea of multiples. I was interested in artists books when I was in art school, and doing something like that. So, that was an influence when I was 20.

Another artist that I like, which for reasons wouldn’t have much bearing on this, although everything does I suppose, Max Ernst was the first person whose work I was really exploring. I liked that he would do something and then stop. Then do something else. I admired that. He stayed sort-of restless and continued working different ways.

In an odd way, I never thought about it, the connection, I mean I have a whole bookshelf of his stuff, Richard Brautigan’s books. He was a popular, not underground, he was more like the popular sort-of hippie writer out of San Francisco in the sixties. He wrote “In Watermelon Sugar,” and he was huge. He was really big. I liked that his prose form was haiku-like I suppose. He would write a story, and it would be four lines, and then next page, another chapter. I really liked not necessarily his voice, but that way of using language. I just liked those books as objects.

I like Eric Craft. But that’s more in the last ten years. All of his books are about one guy who is really him. It’s about somebody growing up in Long Island that’s about the same age as him, and it is him in essence, but he does it without a hint of nostalgia. The books are all not traditional sequential books, but you could read one in any order and in a way they are like sections of your brain. They are all circling around the thing that you can’t make, which is this alternate person. You can start anywhere and read any of them because it’s not about reading them in order. There’s something about that. I like that kind of construction. The best one to start with I’d say is “Little Follies” which collected, he did a bunch of little novellas, and that sort of put him on the map 15 years ago.

Nicholson Baker too. I just thought of him because I just read one of his books. He did “The Mezzanine,” and it got a lot of attention. It came out in the late eighties. It’s all about one escalator ride in a department store from the ground floor all the way to the mezzanine level. It’s all takes place during that much time, so he is always deconstructing the activities of thinking that goes on in your head. So he’s on the escalator and he’s got a bag in his hands. He’s thinking about the feel of the bag, and one thing leads to another. And it’s the whole book. There’s one I just read called “Room Temperature,” that I had never read. It’s one afternoon, he’s in his thirties, a father holding a baby, and it’s like an hour in time. He ends up thinking about the sound somebody makes when they make a comma on a page. It takes delight in the act of thinking and the act of language. His book this year is great, it’s called “A Box of Matches,” and it’s just about getting up to light the fire in the stove, but it’s about what goes on in your head while you are doing it. He came into some fame because when that Clinton stuff was going on with Monica, I think they had exchanged a gift, a book called “Vox” which was by Nicholson Baker, and again it was a very small view of something, and it was about a sex caller, it was two people on the phone, that was the entire book. It’s very graphic and sexual, but it’s not a sexual book.

LK: Will you talk about Slow Fear?

DG: Makes me think of a mild panic. Reminds me of those things that you really can’t put your finger on it, troubling stuff, and actually that stuff is troubling to me, and it happens, certain panic issues, because there is a lot of energy expended trying to figure out what the thing is that’s hanging over your head. Obvious fears are easier to deal with than the panic stuff, because with panic I feel lost. Like the thinking can’t land on what it is that’s bothering me, and if I just knew what it was I could deal with it, but it keeps moving too fast.

LK: What about Black Feather Limbo.

DG: That’s kind of musical. It seems mostly musical to me because of the word limbo. The black feather seems stagy and a bit of exhibition to it. If feels like a music revue, Latin maybe, something danceable, Caribbean, voodoo rituals…

LK: Lamppost and Television.

DG: Together? I don’t usually think of them together. I think of those ads of some guy leaning against lampposts on T.V. Like in an old movie or something. I think the lamppost ends up on the T.V. In the screen. And it’s snowing, that kind of thing. Like a Christmas ad. You see lampposts in all of those.

LK: Pink Fuzz.

DG: Well, first I think of those dice, but then I think there was that flocking stuff, like fuzzy stuff that you could put on a surface, and there was this guy in this band when I was in Junior High school, and was in bands, and he had an amp, a Heath kit, you know the kind you would make, and he covered the whole thing in that flocking. So, fuzz goes to that guy. I can’t even remember his name anymore. The band he was in was The Beach Combers. I remember them.

LK: What about Blue Screen.

DG: That one just sort of flattens out to the information. It’s a nice word, but I guess after the other words this one now all of a sudden just gave me the object. It just sort of came and handed me a thing. What it then makes me think is that it’s kind of a nice word. I’m not used to thinking about it as the word. The words usually disappear with real specific objects, and the object takes its place. Until you are forced to think about the word. I never thought about it, but that’s a kind of a nice phrase. Which then reminds me of something that I saw, I think I was in grade school, in a Weekly Reader or something else, so I don’t remember the format. If it was in a filmstrip, or a T.V. show, but what was imparted whether it was on television or on the page, was that Ben Franklin traveled through time and he was now in the modern day world in the 1960’s. He was taking delight in certain words that explained themselves through the use of the word, and the thing that I always remember is the word “television.” He took that word for everything that it is. It is explaining itself in its definition. And he was delighted by that.

LK: Modern Orange Sky.

DG: It reminds me of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. But he did “Orange Colored Sky.” So, if you say, “orange sky” I just land on that.

LK: Talk about some of the Duplex Planet inspired recordings like “A Place of General Happiness” that integrated musicians and Ernest Brookings’ poetry.

DG: The Brookings things are part of a series. The sixth collection will be out in a year or so. It started because Ernie of the Duplex was an engineer. He was a designer of machine parts, he went to MIT, a really smart guy, who was now a little mixed up, living in a nursing home, and he would always copy poems and recipes out of magazines like Readers Digest and he would give them to the nurses at the nursing home as kind of a gentlemanly offer. At some point I said, “Did you ever write a poem of your own?” and the very first one, he says, “What should I write about?” and I said, “A Trip to the Moon.” The very next day he handed me a poem he’d written called “Planning and Completing an Explorative Trip to the Moon.” With that system in place, he wrote about 400 poems. He would say, “What should I write about?” and his writing was tiny and he was hard to understand, I could understand him, but I would just usually say, “Coffee” or “Chair.” Some object. And he would say “ok” and just walk away. The thing that distinguished his poems, what gives them their character, is that for him a poem had to be a strict A: B, A: B rhyme scheme. There was nothing else. That was the definition of a poem in his engineers approach to it. Every one of his poems rhyme. Some make no sense because he did whatever he had to do to make them rhyme. He would just change the subject, he made up words, and he did whatever he had to. There was this further thing that he did, because I would see the drafts of it, one he had the first line, when he gets to line three if he’s given himself a difficult word like “octogenarian” he never would change it. He wouldn’t put “octogenarian” earlier and end with something else, it was like a trapeze artist with no net. Like “Oh, how is he going to get out of this.” But two lines later he’s just got to rhyme with that. He would just do it. Like with “octogenarian” he would change the setting to “an aquarium.” Even though it made no sense to what was going on.

So the band I was in, Men and Volts had used lyrics that were his for a song. Then I thought other people could do this, so I started asking around for other bands. It just grew from there. The first one then put it on the map, Andy Partridge did one, and Fred Frith, and Ernie lived to see the first one out, he was dead by the time the next one did. Most people got it because they want to have everything that The Young Fresh Fellows do, that’s the way in, but the information is in there about how this came to be. I’m just trying to offer up Ernie as an example of, here’s a guy who towards the end of his life did this new thing. He was perfectly open to whatever odd suggestions I had, like writing poems and me sending them to bands, bringing in little headphones and him listening to it, music he would have never heard and probably had no interest in. And he would write a thank you note, “Thank you for the Rock and Roll rumba synchronization to my poem,” or something.

When the Duplex Planet illustrated that comic series, there was an extra issue that Fantagraphics did that was just all Brookings poems done illustrated, in comic form. But the name of it came from a book that was out, a really nice letterpress company did a book of his called “We Did Not Plummet Into Space,” in the early eighties, and there was an autograph party held at this church near the nursing home where he would go every day for his lunch, and all the ladies there seemed to like him, and they made baked goods, and so it was all of those people, and local Boston musician hipsters all coming to have Ernie sign their book. Ernie, I don’t know how he got the idea to do this, it’s sort of straight out of a celebrity thing, but he had this stock thing that he would write as his inscription, and who knows to do that if you’re not signing autographs all the time? He would write “You have a vast knowledge of general subjects” and he would sign his name. What a nice safe compliment.

LK: You have a website for Duplex Planet now, right?

DG: It’s just a bunch of streets and little buildings, and there is stuff in them. I don’t know, it just seemed good to have a presence there. It’s like a store waiting for people to come to it. Beyond that, its information if I’m going to go do something. I do these performance things, and so it’s good to have one place where there is information. This spring, I am doing another collaboration with some musicians from Portland, and we will do a little tour of the northwest, and we will have a cd out before that. In the fall I’m doing a bunch of stuff in Boston. There are a couple of films, documentaries, and they are Duplex Planet based. One is done my Jim McKay, he did “Lighthearted Nation” and he did it with Michael Stipe’s C-100 Film Corp. And then a couple were done by some guys in Boston that was actually shot on Film, and that’s called “Your Own True Self” It functions differently that Jim’s, that one is almost like an issue of this, people are talking to me but you don’t see me, but I’m there in the presence throughout all of it. I think those are going to be shown at an art house cinema, and them I’m going to do a monologue with music. And there is a band that is going to do a night of The Ernest Noyes Brookings songbook. I always thought it would be cool if one band would just do this stuff. It would give it one voice, because the one thing I set out to do on these compilations, was to make them as diverse musically as I can. So, the thing that links it together is Ernie. On one compilation, you start the thing with Brave Combo, and it’s a cha-cha. It’s all over the map, it’s all over the place, so that you have to think, “What’s holding this together?” and it’s Ernie.There is also a book that was out this year, it’s called “No More Shaves,” which collects a lot of stuff from the comic book series.

LK: Duplex Planet reads a lot like a movie, it’s very surreal, especially because you transcribe the language exactly as it was spoken, without changing anything.

DG: I really want the individual voice more than anything. More than information. That’s why, almost like your word association parts of your interviews, there is some subject that you can talk to anybody about and they will start talking about something. Snakes, or coffee. Somebody will start talking. I feel like one of the things that keeps me on this, and I know that this is my work, what I’m supposed to be doing, there is just this cultural emission about this. When people find out that I do something with old people, they think oral history. There is such a limitation in thinking that. It’s not anybody’s fault, but that is the only way that anybody has to view the idea of aging. There’s somebody old, so let me go talk to them about what happened before I was born. I have no particular interest in that. It serves no purpose to me. I’d rather know what it’s like to be them. The way you really learn stuff is going to somebody and acting like they’ve got the wisdom of the age, and “tell me the secrets of growing old.” That’s just bullshit. You just are around somebody and you learn by being around somebody, and how they carry themselves, and how they respond to things. In fact, I think that whole idea of oral history, which has a purpose, but it’s already been done, that’s as limiting as the other thing, treating old people as wizened old sages, that’s fine to do it, but you’re not going to have a relationship with somebody that you are bowing down to. They are on a pedestal and unless you are eye to eye with somebody you’re not going to get to know them.